By Zach Powers, The Writer’s Center Maryland-based writer Steve Majors recently published his gripping, startlingly honest debut memoir, High Yella, with The University of Georgia Press. He talked with us […]

20 Jun 2023By Kathleen Wheaton

It was February 2020 when Washington Writers’ Publishing House decided to put out a new fiction and poetry anthology—that is, a lifetime ago. A staff meeting at my house: everyone crowded into a small living room, barefaced, handing around mugs of tea and pretzels without thinking about who else had touched them—remember gatherings like that?

Our purpose was to introduce the 2020 WWPH Fiction Prize winner, Adam Schwartz, and the 2020 Jean Feldman Poetry Prize winner, Steven Leyva, to the other members of the press. In addition to having submitted stunning manuscripts, both Steven and Adam seemed like good folks, which is a plus when you’re a part of a cooperative.

WWPH was founded by hippies—their word, not mine—in the mid-1970’s, when four DC poets got a National Endowment for the Arts grant to start a nonprofit publishing house. Their idea was that the poets they published would then volunteer for the press: “poets working on behalf of other poets” was their visionary motto. Their book distribution method, known as Drop-and-Split, involved sneaking into bookstores, squeezing freshly printed volumes onto the shelves, then dashing out to a waiting getaway car.

Despite obvious flaws in the business plan, WWPH has persisted for almost five decades, publishing more than 120 volumes of poetry and fiction. Nowadays, our books are sold in bookstores, not planted like revolutionary pamphlets. And yet much remains as the founders dreamed. The staff is still all-volunteer, comprised of previous winners of an annual blind-judged contest open to writers and poets living within 75 miles of the Capitol. The press functions a bit like a long-running group house, with inevitable hitches but a sense of common purpose. Some people fulfill their two-year responsibility and move on; others—like that guy on the third floor who knows how the boiler works—have been around forever.

It’s a nice community, for one thing. Temperamentally and/or vocationally inclined towards introversion, writers often don’t realize they need a community until one is thrust upon them. Though because the press is small, with barely the human and financial capital to put out two books a year, it can—like a group house or an island nation—become insular.

In 1995, WWPH broadened its reach with an anthology, Hungry As We Are. The 122 DC-area poets gathered in that volume represent a poetic Who’s Who of the late 20th century; the poems themselves—referencing Latin American wars, the fall of Communism, the Oliver North/Fawn Hall scandal—make it very much a portrait of its era.

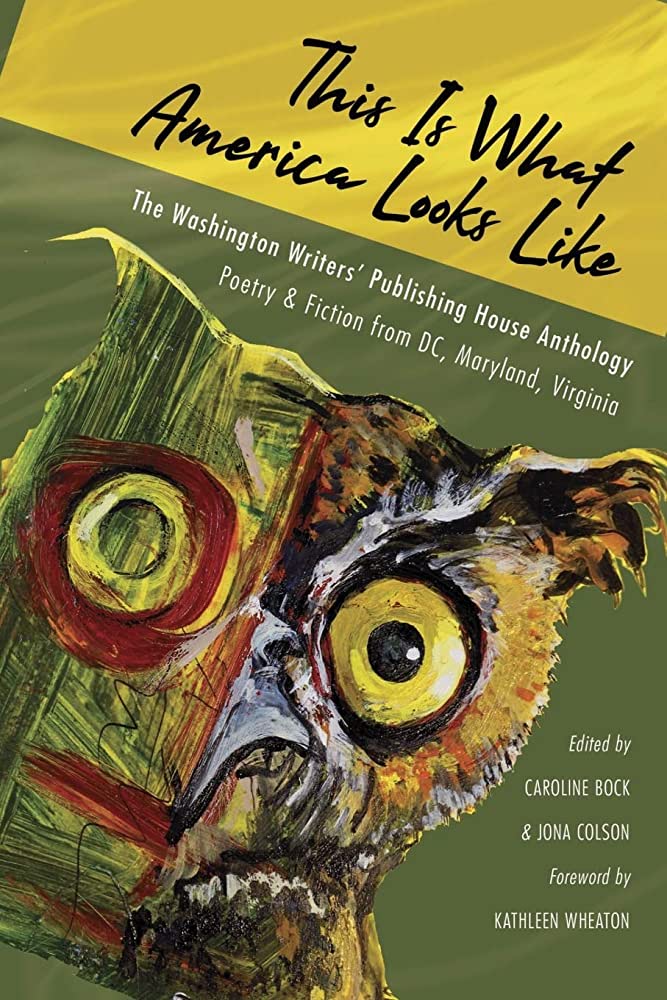

It was at the meeting last February that 2018 Fiction Prize winner Caroline Bock suggested it was time to put out a new anthology. She already had a title in mind: This Is What America Looks Like, the chant that had echoed through the January 2017 Women’s March following Trump’s inauguration. Like the march itself, this anthology should be diverse, inclusive, big, joyous. It should contain both poetry and fiction. We should expand our geographical boundaries to include all of Maryland and Virginia. We should have an eye-catching, colorful cover.

The proposal sounded so right, so optimistic. Financially, we felt as on firm footing as a shoe-string operation ever does: we had events planned for Steven and Adam’s books at Politics & Prose in DC and The Ivy Bookshop in Baltimore, as well as at The Writer’s Center. We agreed to suspend the regular contest for a year to accommodate the work and money the project would consume. The 2018 Poetry Prize winner Jona Colson joined Caroline as the anthology’s poetry editor, and they put out a call for submissions.

It was maybe like planning a group photo in a meadow before a plague of locusts descends, followed by a hurricane. Two weeks later, the world went into pandemic lockdown. A handful of submissions trickled in. Then came the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the Black Lives Matter protests. The trickle of manuscripts dried up. In times like these, we wondered, maybe the whole idea of a literary anthology was frivolous. Maybe we should scrap it altogether.

Hours before the deadline, there came a flood of submissions. “I was astounded and gratified the way the prompt, This Is What America Looks Like, resonated,” Caroline Bock says. “Writers were taking on the big issues of death, of social justice, of the pandemic, of the daily, grinding frustration of our divisive political times.” We had flash fiction from homebound parents and frontline medical workers; poets exploring loneliness and loss in real time. We got new work from writers we admired, pieces by emerging writers for whom the anthology would be a first publication.

“The best thing about editing this anthology was being able to read all the poems that were submitted,” says poetry editor Jona Colson. “Some were more experimental in form and required closer readings. Other poems were more traditional and had a clearer narrative. I didn’t find that a particular style worked better—and actually, having a narrow range of style was something I wanted to avoid.”

Working on a collaborative project in lockdown presented its own problems, Caroline says: “With the pandemic, we couldn’t meet in person. We couldn’t spread out all the work on the table. We had jobs, our families, partners, pets to worry about in addition to this quixotic literary task. We had to trust one another and the words, our own and the writers we accepted.”

In terms of production, almost everything that could go wrong did, during this annus horribilis—delays along supply chains and with the postal service. After the January 6 riot, the Library of Congress closed, briefly halting the issuing of its publication data. Compared to the violence and terror experienced in the Capitol, this was minor, but it wasn’t nothing. It was another reminder of the fragility of institutions we’d taken for granted, before.

It was sheer luck that This Is What America Looks Like made its publication date, February 2, 2021—again, by hours. Contributors didn’t yet have books in hand on February 5, when The Writer’s Center hosted a virtual launch for the anthology. But many attendees ordered copies, and for that we were deeply grateful. Like restaurants, small presses depend mightily upon being able to show people a good time. At a reading, attendees laugh, maybe sniffle, and are moved (okay, maybe there’s subtle peer pressure) to meet the author and buy a book. Getting back into local bookstores, into festivals and neighborhood book clubs, will be crucial to our survival.

At the same time, This Is What America Looks Like has thrown open the doors and windows of WWPH, and we’re determined to keep them that way. We plan to publish new short stories and poetry bimonthly on a revamped website. Having learned to work and collaborate over Zoom may mean that we can expand our geographical boundaries permanently. We cast a wide net with this anthology having no clue what was about to befall us. That it came together is thanks to the alchemy of community, and we want to ensure that the voices gathered will be heard again, loud and clear, in the post-pandemic world.

Kathleen Wheaton worked for 20 years as a freelance journalist in Spain, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Bethesda, and now interprets Spanish and Portuguese for Montgomery County Public Schools. Her fiction has appeared in many journals and three anthologies, and she is a five-time recipient of Maryland State Arts Council grants. Her collection, Aliens and Other Stories, won the 2013 Washington Writers Publishing House Fiction Prize. Since 2014, she has served as president and managing editor of WWPH.

Originally published in The Writer’s Center Magazine.