By Zach Powers, The Writer’s Center Maryland-based writer Steve Majors recently published his gripping, startlingly honest debut memoir, High Yella, with The University of Georgia Press. He talked with us […]

20 Jun 2023By Priyanka Champaneri

After graduating from college in 2005, I worked an office job full time while taking graduate creative writing courses at night. I didn’t quite know what I was doing with myself or my life, but I knew I loved books, with a passion that has run unabated since I was a child sitting up in bed reading, not noticing that hours had passed, the sun had gone down, and perhaps I should turn on a light. Then—and in some ways, even now—writing a book has always seemed like an impossible thing, but taking a class was a smaller commitment that I could handle. I passed my days between work and school with hours of reading and dreaming and thinking, filling the spaces between.

During that time, a friend sent me a message with a link to a Reuters article titled “Check in and Die in Two Weeks, or Get out.” As I read the article, which detailed the death hostels of Banaras, including their function and their necessity, I felt my interest catch, but I tucked the email into a folder and went on with my day. I was intrigued by Banaras, a city on the river Ganges in northern India, but my knowledge of the place was limited to its appearances in what I had read as a child—the Amar Chitra Katha comic book versions of The Mahabharata, Savitri, and Tales of Shiva; K.M. Munshi’s Krishnavatara series; and the many fairy tale collections curated by Andrew Lang and Joseph Jacobs. Those stories mentioned the city under its spiritual moniker of Kashi, and I confess that I thought of it more as a setting for fairy tales than as a real place existing in a modern world.

I also felt overwhelmed by how much India held that I still did not know. It is impossible for any one person to thoroughly know her country, even if she is born in the place her people have called home—but I think for those who are born away from their homeland, the need to know everything about the place, no matter how vast and how storied its history, can become a mission, a way to earn a place of belonging. I wasn’t prepared to push that particular rock up a mountain. A few years later, I had left my job and was in my first year of graduate school in an MFA program, and one of my assignments for class included writing the flap copy for a potential novel that I might write. I reached back into my memory and pulled that article out, and I felt that long-ago interest catch at me once again. I was still overwhelmed at the thought of writing about a place and a community I could not call my own, but this was only flap copy—and so I wrote out a 100-word synopsis for a book set in a death hostel.

A few months later, for the same class, I wrote the first chapter of the book I’d envisioned in that flap copy. But that was only an exercise, a place for me to play and dream, never something that might become real, because who was I—a person who had been to India twice, but never to Banaras, and who was Indian in blood and name and spiritual heritage, but perhaps nothing else—who was I to write about this city?

It was easy to bar myself from that space, and so I did. And yet I saved the issue of Little India magazine that came to my house, with its feature story about Banaras. I placed a bookmark in the chapbook of Ramprasad Sen’s poetry to mark “Tell Me Brother, What Happens after Death?”, a poem whose lines ran through my head on an endless loop. I watched Forest of Bliss, an almost wordless documentary about Banaras that showed me a city entirely real and modern, yet—to my mind—frozen in a time unto itself. I flipped through public television channels and somehow landed on a rough travelogue based in Banaras. I bought a copy of End Time City and felt as if ghosts were wafting up from the pages of Michael Ackerman’s photographs as I gazed at each one. I watched YouTube videos of people doing nothing more than holding their smartphone cameras up as they walked through the winding narrow lanes of the city, recording the sights and sounds of all that they passed, a trompe l’oeil of cinematography that made me feel as if I were the one walking those lanes, absorbing the city’s sighs.

Whether by accident or by chance, the city sought me out, and I grasped at everything that came my way. And though I still felt I had no right to create work about a space I did not belong to, my brain continued to hum on its own, with no qualms. More insistent than my fear of not knowing enough were the questions drumming their way through my head, questions I’d pondered for years about death and reincarnation, about forgiveness and redemption, about the capacity of every single person to live multiple lives within the single one they occupied at that present moment. Finally came the point, midway through graduate school, when my fingers and my pen also thought, as I had more than a year before—why not? Why not write some words down, and see what happened?

And so, I did. I wrote, and the pages I produced by the time I was set to graduate became my thesis. I got another full-time job, and I continued to write. Self-doubt crept in daily, but when the words flowed, I felt that even if I did not belong to Banaras, even if it did not belong to me, at least the story and the characters did, because each day I put pen to paper, I understood a little bit more about them. And I wanted to find out what would happen to them. In the end, any motivation I had to continue writing was driven not so much by self-discipline or any kind of belief in myself or confidence in my understanding of the city. Instead, I was propelled by the thing that made me continue to turn the pages in bed all those years ago, long past the time when the light from the windows was enough for me to see the words on the page, one question at the forefront: What happens next?

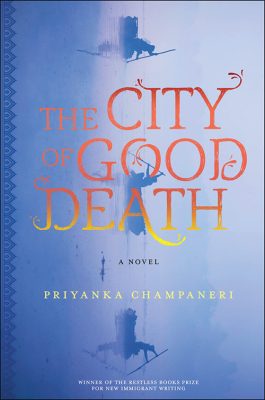

It’s a question that took me more than 10 years to answer. By the time I finished, the story I discovered was very different from the one I’d written flap copy for years before. But my intentions, from hesitant first words to sure-footed last lines, remained exactly the same: The City of Good Death is my love letter to the city, a book that I hope holds some seeds of recognition for the people who have been there, and some seeds of wonder for the people who have not.

Originally published in The Writer’s Center Magazine, Summer 2021