Adult Short Story Contest – 1st Place RubinaBy Asma Dilawari – Bethesda, Maryland The kettle whistled and she poured the boiling water over tea in the saucepan, recalling one of […]

17 Jul 2025

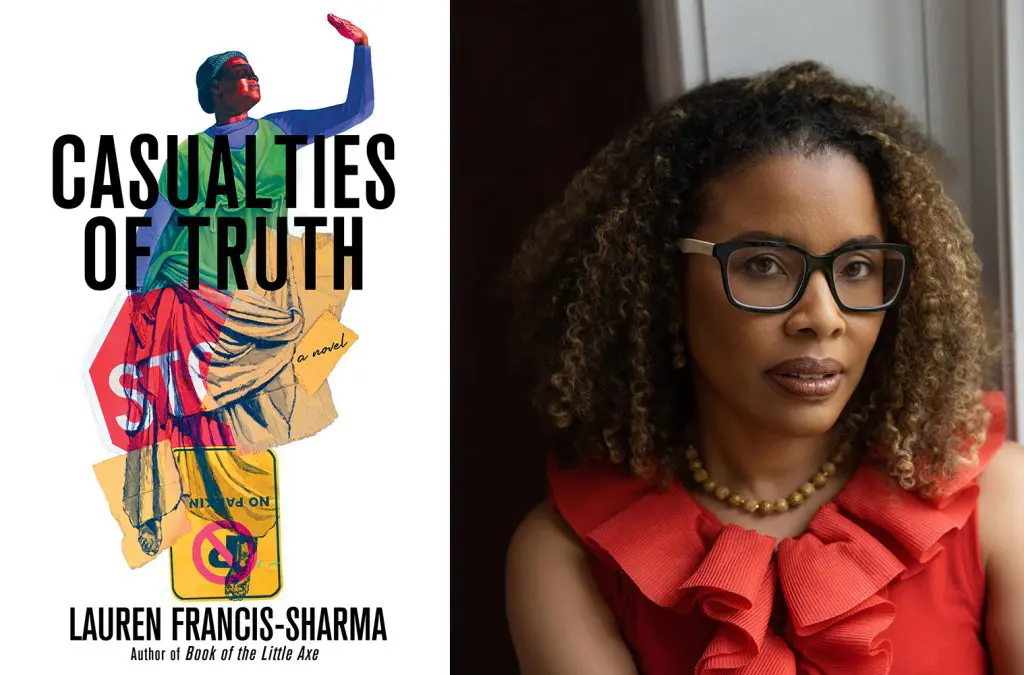

Lauren Francis-Sharma’s new novel, Casualties of Truth, is both thrilling and thoughtful. I’d also call it timely — but as an author myself, I know that by the time a book reaches the public, it can have already existed, in some form, for years. Still, some of the book’s themes, rooted in South Africa in 1996, remain resonant. So maybe instead of timely, the right word is timeless. Lauren was kind enough to talk with me about how this entertaining and enlightening book came to be.

ZP: I think it’s always interesting to discuss why writers choose to write what we do. Approaching this from a writer’s perspective, what was the origin of this book? Why this topic and these characters, why now, and why this instead of something else?

LFS: If there was any gift that Covid offered, it was the gift of time. I spent many hours dreaming of leaving my home and one of the ways I coped with being in lockdown, was forcing myself to remember the places I’d visited in my life and the stories I’d accumulated in my travels. Recently, I heard Alexander Chee in an interview where he was encouraging nonfiction writers to focus on writing the stories that they often repeat at cocktail parties. While listening to Alex it occurred to me that my law school internship in South Africa, when I was 24 years old, had become my very unsuccessful cocktail party story. I say “unsuccessful” because I never quite figured out what the experience of being there meant to me, and so the story always felt incomplete when I told it. During Covid, I had time to think deeply about that particular story, think about what it meant to bear witness to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Amnesty Hearings and for people to actively seek a way past immense pain. My main character, Prudence, like me, interned in South Africa just as the hearings were beginning. When we meet her she has run into a man, Matshediso, whom she knew from her time in Johannesburg. He turns up at an intimate dinner, quite unexpectedly, and Prudence finds herself in the most challenging situation of her life. Prudence embodies all the uncertainties and hopes of a post-Apartheid South Africa, and she must reckon with the fallout from that period too.

The first part of the book is told in alternating timeframes. I’m always fascinated by how parallel narratives work, and how the separate storylines work together to achieve something that one or the other might not on its own. First, how do you approach writing parallel narratives — do you bounce back and forth or do you draft each independently? Second, how did each of these sections a¤ect the other? Is there anything that you discovered because of their juxtaposition?

First, let me say that employing alternating timeframes is far simpler than employing alternating timeframes coupled with multiple POVs! I used that structure in my last novel, Book of the Little Axe and would not recommend it! And yet, I’m drawn to narrative jumps in time because this is how the human brain seems to work. Think about how I answered your previous question — there I was, living my Covid lockdown life, but also living in South Africa as a younger woman, reliving my first safari, my first white-water rafting trip in Zimbabwe, and sitting in the balcony of the City Hall building, listening to accounts of Apartheid horrors. So, of course, it felt natural for my character Prudence to experience this same mode of thinking. Perhaps the reason I’m so drawn to history, and maybe even to writing itself, is that I need time to process what I see in the world, to formulate my questions. When Prudence meets Matshediso again, it frightens her to feel her past and her present converge, and immediately she is thrust back to Johannesburg, thinking of the experiences she and Matshediso shared. Of course, she can’t stay in this state of reverie during the entire dinner, so she has to be pulled out when the present moment requires it. So, yes, I bounce back and forth, but what’s essential is that for the ins and outs of this remembrance to work, it must be triggered by something, and the execution of this transition must feel like a natural extension of the present story. These transitions certainly allow Prudence (and me) to see just how much her time in South Africa changed her and just how similar the experience of being in South Africa is to being in America, in good ways and in not so good ways.

The novel draws from your experience witnessing South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Hearings, and I assume a fair bit of research on top of that. What’s your process for turning the bare facts into an interesting, gripping narrative? Conversely, how do you prevent the narrative from becoming fact-heavy or didactic? How do you achieve that balance?

I mentioned earlier that I started thinking about my time in South Africa during lockdown, but what I didn’t mention is that I went into my basement searching for notes that I had taken during the Amnesty Hearings. What makes someone keep notepads filled with transcribed testimony for nearly thirty years? The answer is the stories. I couldn’t throw away the stories of people who had lived through the terror of Apartheid. My cocktail party story always included the group of boys who had been lured to their death by a Black, undercover, South African Police operative. Their parents were in the audience while I was there, and it was the first time they’d heard the account of what had happened to their children. It was horrifying and gripping, and I’m not sure I could ever properly convey what it felt like to be in that room, listening to former police agents speak about murdering children, but I tried to do so through Prudence. I put her there so she could absorb the bare facts into her personal narrative and show how witnessing something like that changes the entire way someone sees the world and sometimes the very trajectory of a life if that someone allows themselves to be changed by the stories of others.

I’d call this novel a literary page turner. What advice do you have for writers about keeping the prose robust while maintaining narrative forward motion?

I certainly wanted to write this so you wouldn’t want to put it down, so I’ll happily accept “literary page turner” as the description for this novel! Thank you! But I also love long sentences and I love forcing my characters to take note of the natural landscape around them. If you’ve read my previous books, you know I strive for vivid scenes and I’m not afraid of long sentences. With this book, I had to ensure that every one of those scenes and sentences was earned. In the opening of Casualties of Truth, a South African police officer leaves his house when it is still dark. He realizes his tires have been slashed and as he walks along his driveway, buffalo thorn tree buds fall and he crunches them beneath his boots. I don’t pause long enough to describe the tree hanging over the driveway, but because he’s stepping on buds, the hope is that the reader visualizes the tree. I had to be more economical in this book, but I also tried to deliver the same vividness that I have always delivered.

This is book number three. I wonder if you’re able now to look back and see things you’ve learned along the way? What processes and techniques did you discover writing the first two books that informed writing this one? In the opposite direction, what parts of the process have been new each time?

Many other writers have said this, but the thing you learn when you get to book three is that you can actually write a novel. Ha! With that said, I failed at writing the novel I started just after Til the Well Runs Dry. I thought I could figure it out and I still think I can, but I’ve concluded that it is simply not the right moment for that book. There are times when the story or something about the character comes easy to the writer, so that you can feel the energy of it in your fingertips, feel ideas unfolding before you as you write or even as you think about the story while doing something mundane like washing dishes. That, of course, doesn’t mean you don’t have long moments of uncertainty or digression, it just means that more often than not, you hit the flow. I’ve learned to trust that flow. But even with this said, every time I begin, I think about how I cannot believe this doesn’t get any easier! I am stunned when I start a new book as I realize once again that there is simply no way around spending months or years in the same chair trying to reveal something important about the world to strangers. It is magic. And it is also hard.

As Assistant Director of Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, I bet you get to experience a lot of amazing writers talking about the cra£ of writing. Since we last interviewed you in 2020, do you have any new or particularly interesting writing advice you’d like to share?

I have the incredible luck to spend ten days every summer with the most amazing writers who come to a mountain in Vermont to teach and learn about the craft of writing. Many of our lectures and readings are free online, accessible to those who want to listen. This summer, Garth Greenwell was with us and he did a lecture on James Baldwin, where he said something like, “We live in the irreparable. We need art to help us live in the irreparable.” That has stayed with me. The art gets us through the worst of our days. The music, the movies, the books, the art of humans, and the art of nature, make each day bearable and sometimes even injects it with joy. My novel is so much about confronting the irreparable and in it there are moments of joy too. I hope one day it may be viewed as a piece of art that helps us see and cope with the irreparable.